It is not unknown to me that many have held and hold the opinion that worldly things are so governed by fortune and by God, that men cannot correct them with their prudence, indeed that they have no remedy at all; an on account of this they might judge they need not sweat much over things but let oneself be governed by chance.

– The Prince

Wisdom-based problems are free response rather than multiple choice.

– What is Wisdom? A Unified 6P Framework

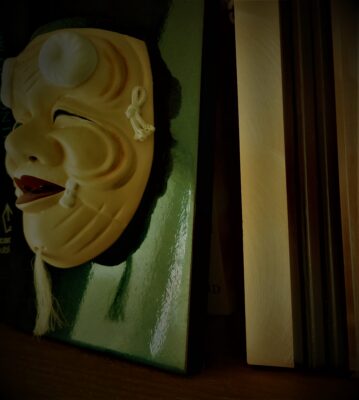

In traditional Japanese theatre, masks are worn. The masks represent archetypes and the form they take is representative of a consensus view on distinctive features of such archetypes. People generally think of an old man with a long white beard regardless of culture as a symbol of wisdom. Is it true that wisdom is a product of age?

Age implies experience. Implicit in the usage of the word experience here are connotations of loss – once bitten twice shy. Acquiring wisdom after loss is like being shown the answer key after getting it wrong. The answer key is of no use in preparing for a test. If this analogy is valid, there are two implications.

First, there is no need to chase after wisdom since problems and loss visit everyone. Secondly, wisdom should be esteemed only to the extent answer keys are.

Both implications though appear counter-intuitive and wisdom is valued highly for a number of reasons. Such reasons relate to a range of domains, from the neurobiology of an individual to solving existential threats facing humanity.

For instance, Grennan et al., (2021) found wise people were generally happier because they paid more attention to positive stimuli than others. If you stopped at the preceding sentence because of cognitive dissonance, it is understandable. Science is about measurement and we would think wisdom is intangible. Who were these wise people in the experiment?

The subjects in this study were “147 human subjects sampled across the adult lifespan” (Grennan et al., 2021) from 18 to 84 years of age. Researchers could sieve out the wise among this pool by analysing responses to the San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE). SD-WISE was developed in 2017 after being tested with 524 participants aged 25-104 from the San Diego County (Lafee, 2017). The SD-WISE comprises a number of statements which measures different aspects of wisdom. For instance, under Pro-social Behaviours, a statement reads, I would stop a stranger who dropped a twenty-dollar bill to return it. The SD – WISE has been adjudged reliable as a measurement tool for wisdom. If you’d like to participate in ongoing wisdom research by the same people who developed SD-WISE, you may do so here.

Grennan and others’ (2021) experiment entailed asking subjects to look at positive and negative facial expressions. Subjects’ electrochemical activity in the brain was measured with EEG and they observed, “significantly enhanced alpha band activity in the left insula during happy emotion biasing”. Those with high scores on SD-WISE spent more time looking at happy facial expressions. The researchers added that “the insular region is critical to both emotional and cognitive attention, self-awareness, and empathic regulation”.

Wisdom is not merely theoretical and abstract. It involves “knitting together the cognitive, social, and emotional processes involved in everyday decision making – i.e., actual decisions and choices one might make” (Nusbaum, 2016 as cited in Thomas et al., 2017). A wise person makes better decisions. Many decisions require wisdom. This much is accepted. Do students have to wait till after experiencing loss to become wise? Can wisdom be taught or is it acquired?

In a recent publication to introduce a model to describe wisdom better, Sternberg and Karami (2021) suggest that the problems of the 21st century which range from pandemics to WMD require wisdom and that students should be trained to be wise from a young age since “children and adults both can be taught to be wiser through case studies and other methods designed to help people reflect on life problems and how they can be solved effectively”.

They conducted a comprehensive literature review of the concept, including in their analysis the philosophy of eastern, middle-eastern and western cultures.

They highlighted the multi-dimensional scaling analysis of Vivian Clayton who asked her participants to “generate a list of descriptors for a wise person”. She found that people generally thought of a wise person as, “experienced, intuitive, introspective, pragmatic, understanding, gentle, empathetic, intelligent, peaceful, knowledgeable, (with) a sense of humour and observant”.

A similar attempt to document the commonly assumed personality traits which embody wisdom by Hershey and Farrell (1997) led them to suggest, “wise people are withdrawn, quiet, reflective, and that they show an absence of ego-tism”.

These studies were conducted in the west. To be sure, these qualities were what respondents thought wise people were like. Whether such people actually exist is a different question.

They also highlighted eastern conceptions of wisdom. For example, the Japanese thought that wisdom comprised, “knowledge and education, understanding and judgement, sociability and interpersonal relationships and an introspective attitude”.

The middle-eastern conception was distilled from understanding Iranian perceptions. Iranians believed, “being faithful, thoughtful, rational, tolerant and lenient, knowledgeable, kind, having respect for oneself and others, farsighted and intelligent are other characteristics of wise people”.

Combining these findings with that of Grennan and others (2021), it is understandable why depictions of wise figures generally show them to be contemplative by stroking (to stimulate thinking) the white (to show experience) beard, with a smile on their face. Given the much-needed update in people’s thinking with regards to gender roles, it may be time to develop or make as popular a female version of the sage.

Sternberg and Karami (2021) called their model 6P:

– Purpose of wisdom

– Environmental or situational Press that produces wisdom

– Problems which require wisdom

– Cognitive, metacognitive, affective and conative (motivational) aspects of wise Persons

– Psychological processes underlying wisdom

– Products of wisdom

In essence according to 6P, the purpose of wisdom is to balance interests in order to achieve the common good. What is considered wise will depend on what the environment an individual operates in, considers wise. Accordingly, wisdom may look very different based on where one is from. Problems which require wisdom are different from problems which require intelligence, are “ill-structured” and would need “inferences about the entire situation”. The only commonality among wise persons is that they add to the common good. Processes of wisdom include, ability to balance interests and ethical principles and self-transcendence. Products of wisdom can be domain specific; for instance, when “children learn to act towards others as they would have others act towards them”, be shown in all aspects of everyday behaviour, be passed on from one professional to another and finally entail solutions to make the world a better place.

Unfortunately, Sternberg and Karami (2021) conclude that though there are different scientific views on how wisdom develops, the “bottom line is that after two decades of serious research on wisdom, the pattern of changes in wisdom with development is not entirely clear”.

If we turn to religious texts, some suggest that the purpose of wisdom is to be untouched by suffering and that the way to achieve this is to not chase after gain. Others suggest that wisdom is primarily to avoid loss and proffer a list of maxims towards this end. Various cultures have doctrines which are really strategic or tactical in nature like the game theory of mathematicians.

What we do know is experience has the potential to build wisdom. To the extent that people have similar motivations and drives, the fact that there are only so many things, people want and need coupled with the limited range of possible ways to get such things, people’s experiences would be similar, thus the human condition. Since what we are about to experience or are experiencing has already been experienced by many others over the ages, there may be ways to obtain wisdom at a younger age and without loss.

There may be those who dislike being told what to do and how to think. They may want to be able to take the chance on their own. A way which might appeal to them is to learn about archetypes and patterns from the experiences of others and then to identify such archetypes and patterns in their own lives.

The other way is to be resolute about saying no to illusions. For instance, in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, Shylock’s daughter Jessica is upset and Lorenzo tries to cheer her up and create a joyous mood by playing music. Her response was, I am never merry when I hear sweet music. To which Lorenzo replied, The reason is, your spirits are attentive. What he was in fact suggesting was a distraction and to participate in an “illusion” (Picker, 2001). Illusions of course would alleviate pain in the short term but are not a real solution.

This is how the two ways could work hand in hand to result in wisdom. A person has some want. He identifies a potential item which could satisfy that want. Generally speaking, even though it is said that fortune favours the bold, it is also said that fools rush in where angels fear to tread. If such a person, is familiar with the distilled wisdom from various sources, he could ask if this item fits any archetype and if the events surrounding him fit any known, undesirable pattern. If he does identify such a pattern, he has to be willing like Jessica to not persist in an illusion.

When watching a feel-good play unfold, it is important to be clear-eyed.

The Brain Dojo