In short, as children become older … (they are) more likely to recognize and attend to the relevant information, understand the concepts that are involved, remember the important details of the event, integrate the information, make inferences from it, and apply and understand the relevant social rules.

– Children’s Reactions to Apologies

Young children are often socialized in apologizing by adults’ prompts to deliver apologies, which may not in itself teach children to connect apologizing to feelings of remorse.

– Apologising in Elementary School Peer Conflict Mediation

The Good Childhood Report is issued by the Children’s Society in the UK. One of the aims of the research which contributes to this report is, as the report states, “to make sure the conditions are right for long term growth in the happiness of our young people”. The 2021 version begins with an explanation about well-being.

It states that overall well-being comprises aspects such as self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationships, autonomy, purpose in life and personal growth. One of the “factors associated with children’s subjective well-being” (Good Childhood Report 2021) is Friends. Subjective well-being is measured through children’s own accounts of their levels of satisfaction with different aspects of their lives.

In Japan, concern has been expressed over hikikomori which according to Davis (2018) is a person decides to “avoid social situations” and “locks themselves away in their bedrooms sometimes for years”. A 2019 article was titled What’s behind the Rise of Recluses in Japan. Discussions on this societal issue have generally converged on the causes. One suggested reason for the self-imposed withdrawal is that hikikomori find it difficult to maintain positive relationships.

Maintaining positive relationships is important for overall well-being and requires social-emotional competencies. The framework for 21st Century Competencies (MOE) highlights 5 key social-emotional competencies which are, Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Responsible Decision-Making, Social Awareness and Relationship Management.

While these competencies are social-emotional in nature, language ability is important to hone them. Competency in language is required to put into words (in one’s own mind or to others) the contours of a negative emotion and what it reveals about one’s beliefs and event appraisal. The ability to use language is also important to manage relationships – to head off or resolve conflicts in a healthy manner which crucially approximates an equitable “balance” (Korpela, Kurhila & Stevanovic, 2022) within relationships.

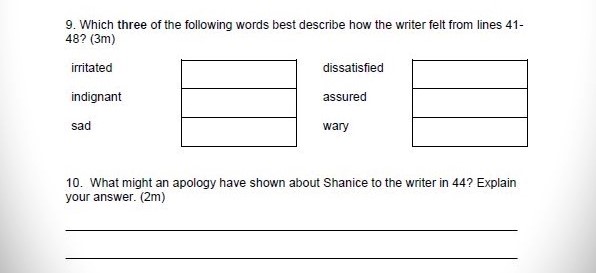

When children get into a dispute, they might turn to an adult to adjudicate. Fact-finding would follow and they may be asked to direct an apology towards each other or towards the other.

In Finland, three researchers conducted an interesting study on how and why children apologise to each other when an adult intervenes. They say that an apology has to be sincere and perceived to be sincere for “repair” (Korpela, Kurhila & Stevanovic, 2022). They cited Robinson (2004) – The sequential organization of “explicit” apologies in naturally occurring English and explained that for an apology to be sincere, “initiative, agency, autonomy, subjectivity, and a personal inner state fit for the action”. This means that those apologising have to be able to do it on their own terms in the way which feels right to them.

At the same time, the researchers added, that apologies are also “rituals” for children in the sense that when an adult intervenes, children are expected to follow rules of turn taking and offer an apology in a form of words and at a time decided by the adult. They wondered if a child who apologises to a peer because of a direction by an adult, can be perceived as sincere since the apology would follow an instruction instead of originating from within.

The researchers studied how primary school teachers in Finland could conduct dispute resolution between their charges in a manner which facilitated both the expression of sincerity and conformity to cultural norms – apologising when being asked to apologise. The researchers termed the form of dispute resolution conducted in Finnish primary schools as mediation.

Mediation generally requires an objective and neutral third party. Korpela, Kurhila and Stevanovic (2022) citing other researchers, say through mediation (teacher in the middle thrashing out the issues between kids who are in a dispute) “children gain competence in culturally appropriate ways of interacting and learn to experience empathy and manage relationships”. It comprises “uninterrupted storytelling” and “achieving consensus on the resolution” (Garcia, 1991 as cited in Korpela, Kurhila & Stevanovic, 2022).

As described by Garcia (1991), mediation is resolution focused and forward looking and some forms do not require any fact finding so long as disputants can agree on a satisfactory resolution. In some forms of mediation, there is no attribution of ‘fault’ and an apology may not be part of the resolution.

Mediation in Finnish schools, at least from the way the researchers described it, typically results in an apology and the ritual is complete when the offended student accepts the apology. The researchers followed 17 teachers in schools from 5 districts mediating conflicts between children aged 7-12 and recorded 19 mediations.

Usually, a student would appear before a teacher accusing a peer of some offending conduct. An interview would follow with a view to establishing an agreed set of facts. While in some instances, agreement on the facts can be achieved through the story-telling with some teacher prompting, there would be occasions where the student who is accused of the offending conduct would flatly deny the other’s version of facts.

After the story has been established, the teachers would typically ask if the offending conduct was done on purpose or by accident. When students say they chose to do what they did, the teachers would then direct them to apologise. Primary school students may struggle sometimes with voluntary acceptance that they have done wrong and, in such cases, sometimes they may have inadvertently revealed facts during their turn to tell the story, which suggest that they were in the wrong. The teachers then would take a more insistent approach in eliciting an apology. According to the researchers, in Finnish pre-schools, a voluntary acceptance of blame is not required before a teacher decides to ask a student to apologise.

According to the researchers, it is when students have each said their piece and when the story has been more or less established that, the one in the wrong would and should be able to see that what he or she had done was wrong. When the action is “evaluated” as wrong, the ensuing apology would reflect that understanding and corresponding remorse.

In this way, the researchers say that the ritualistic process of dispute resolution in Finnish primary schools, achieve both sincerity and conformity with formal expectations.

So crucially, for an apology to be and come across sincere, wrongdoing has to be recognised and acknowledged.

For students to enjoy positive relationships they would need to know when an apology would come across sincere and they themselves would know if an apology is due.

An apology though may not in itself result in the maintenance of positive relationships. Conflicts are generally about protests about the way someone meets a need. Exploring needs (or interests) and healthy, societally acceptable ways to meet needs is also necessary.

An apology is known in linguistics as a performative – where words are also actions.

To say it is to do it.

The Brain Dojo