With all of this evidence that generating errors helps learning, one might wonder where we got the idea – so entrenched in our educational system – that error generation is bad?

– Learning from Errors

Our thoughts and feelings often seem true to us, so it’s important to remember that they’re just thoughts and feelings, not facts.

– Don’t let your emotions run your life, for teens

What do students think when they see that they have made mistakes on their assignments? I could have gotten that right. I was so close! Are you sure that is wrong? I knew I’d get it wrong. I’m a poor performer. I’m bad at this. How could I have missed that? I’ll get it right the next time.

If an answer has been marked wrong, it could have been marked wrongly for all the right reasons, chiefest of which is that markers are human. This does not then strengthen the case for automated marking. Automated marking in its current iteration may not allow for alternative interpretations of questions or answers which are valid but which were not thought of prior to entry into the software. To reduce errors, when it matters, there is usually more than one marker especially when it comes to subjective evaluations.

Evaluations or marking can be subjective as in the case of continuous writing though every effort would be made to ensure objectivity especially when there are stakes. Marking can be wrong. For these reasons, it is intuitive to first ask why an answer has been marked wrong.

There are two ways to do this. First, it is to try to spot the mistake if any in reasoning to arrive at the answer which has been marked wrong. The second is to follow the correct reasoning to get the expected answer. According to Metcalfe (2017), a Professor of Psychology at Columbia University, who specializes, among other things, in learning and memory, thinking about the reasoning behind answers especially when they are wrong, is important to learn well.

It will therefore be useful to explain why answers have been marked wrong. Understandably, this can be a tall order because while the correct answers to a question are very limited, there can be any number of wrong answers for as many reasons. It will be far more time-effective to explain the reasoning behind the correct answer during the post-exercise discussion.

This however, according to Metcalfe (2017) may not be as helpful in helping students avoid following the erroneous thinking pattern which led them to a wrong answer, in a non-identical future exercise. Students will need to understand the errors in their procedures or reasoning in order to not make the same mistake.

To illustrate, she compares American and Japanese classroom practices. She prefaces the comparison with the observation that Japanese students perform quite a bit better in Math. She then goes on to suggest that this difference in performance is because in American Math classrooms, all the focus is on error-avoidance.

American teachers explain the correct procedures to arrive at the correct answer before students attempt exercises. If students were to answer wrongly during a discussion, the teacher may simply look to another student for the right answer, without acknowledging the wrong answer. The foregoing must be a generalization and as a general principle, all generalizations must be taken with a pinch or ‘punch’ as Lefty in Donnie Brasco might say, of salt.

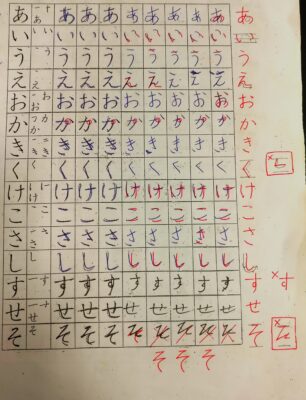

In contrast, Japanese students, “first try to solve problems on their own, a process which is likely to be filled with false starts” because the belief is that, “time spent struggling on their own to work out a solution is considered a crucial part of the learning process” (Metcalfe, 2017). A large part of Japanese Math lessons then, is spent focusing on why the methods or reasoning used during when students were trying on their own were wrong. Only then are the right method and solution presented.

Errors are a valuable part of any effort and students would benefit from not only thinking about their errors but as it turns out, also from making them. Some insights from Metcalfe’s research are as follows.

Students do not forget the correct answer if they had had very high confidence in an answer which they found out was wrong. This means they have to be given the chance to make an error. If they initially did not know and steps were taken to make sure they would get the answer right before they answered, they may not remember the correct answer during exams. The feeling of surprise that they were wrong is crucial.

Neuroscientists using event-related brain potential studies, found that there was an electrophysiological response in the brain, by way of a “voltage deflection – the P3a” which indicated surprise, when students found out their answers were wrong. The P3a was stronger when the error had been made with a very high degree of confidence.

Metcalfe and her colleagues had also in 2012, used event-related magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to find out which regions of the brain were activated when feedback was given to rectify errors which had been made with great confidence. They found that the “anterior cingulate – an area related to surprise, error detection and attention” was activated along with other medial frontal areas which are responsible for, among other things, reasoning and emotions.

What this suggests is first, confidence and accuracy are separate and in fact in the case of exams, may be negatively correlated. Metcalfe points to research which shows students who are overconfident or very confident, either stop studying an area or are too easily satisfied with their answer during exams. To counter this, “post-mortem analysis” or “prospective hindsight” may be useful. Students have to imagine that their answer has already been marked wrong as they are answering a question. Then, they have to ask themselves why and try to reason again to an alternative answer.

It also suggests that it is very possible to be very confident and yet wrong. When this happens, students may get very surprised. This surprise will go a long way in ensuring they remember the correct answer down the road.

Students may prefer not to try on their own before finding out how exactly to get the correct answer because getting it wrong can be emotionally taxing. Also, since during every lesson, new content may be covered, correcting the errors of previous lessons may not be a priority. Students may then receive a worksheet, take a brief glance and file the worksheet. What goes in the file, stays in the file, neatly filed away both physically and in the mind.

For these reasons, students may not be engaging enough with their errors. They can begin to see that errors are learning instead of as evidence of a lack of learning. The value in every worksheet is the errors made and the feedback received in relation to them.

Feedback should ideally focus on reasoning, be affirming and discussed at length with students. Otherwise, they could go,

It’s all Japanese to me.

The Brain Dojo