The ability to interpret assessment data for formative and summative assessments is now an essential skill for teachers to enact good assessment practices in the classroom.

– Assessment in Singapore: Volume 4, Getting Ready for the 2020s

For example, through reflection, students could identify the areas that were not clear, look for the best strategies of completing their tasks, and identify the areas that were neglected by students.

– Reflection in Learning

How does improvement happen be it in answering a certain question type or in any component of the different papers of the English Language exams? Time is certainly a factor. There are times, we realise we are better able to perform something after we have spent time engaging in that something. To that extent, improvement is unconscious.

In what some might consider New Age doctrines or a renewed interest in age-old practices, the focus is on visualisation. The advice for improved performance in such doctrines goes something like this – see yourself doing it right and you will see yourself doing it right.

Coincidentally two books which dealt with this both used the example of the Authentic Swing in golf. The first of these is The Legend of Bagger Vance of which this tutor owns a second-hand copy. The seller, a bespectacled, elderly man who appeared to be in no particular hurry one sultry afternoon, explained that Bagger Vance was a reference to Bhagavan – or God in the Vedas. The second of these is The Magician’s Way (also from a second-hand bookshop, a different one) by William Whitecloud who runs the Natural Success Programme, which aims to help people do what they thought they could not.

In both books, the protagonists struggle with executing a golf swing which would have been satisfactory or demonstrative of skill. They both come in contact with a mentor. The mentors tell them to not look at themselves at all and to think of nothing concerning themselves – not how the golf club was held, not how the stance was, not the strength of the swing; nothing at all relating to performance demand. Instead, they were asked to imagine a perfect shot and to hold that image in their mind when they were taking the shot. This appeared to work like a charm. According to the mentor in The Magician’s Way, “There isn’t anything in life you can’t do with what I taught you today.”

The lack of self-consciousness (which has been known to hamper performance) aside, improvement requires other things. It happens over different phases or stages. If students are familiar with these stages, they would be able to take control of their learning and be confident in expecting to see progress because they now know that improvement is a natural consequence of progressing through these stages.

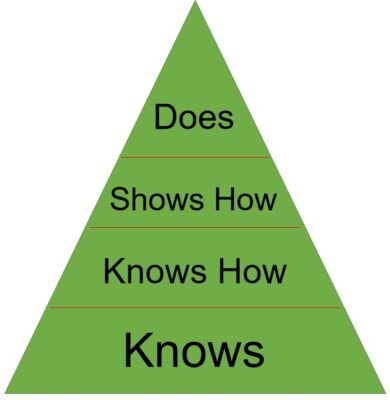

In, Assessment of Skills, an essay in an SEAB publication on assessment, the writer set out to answer, “How can we assess (and teach) knowledge-based skills for transfer?” In his answer, he referred to the Miller’s Framework for Clinical Assessment which George E Miller, a doctor and a celebrated medical educator, conceived of, as a way to holistically (comprising every aspect required) assess if medical students had all it took to be “successful physicians” capable of delivering “professional services” (Miller, 1990).

The Miller’s Framework for Clinical Assessment is decidedly elegant in its simplicity and is presented below.

Miller’s Framework for Clinical Assessment (1990) (as shown in Assessment of Skills, 2020)

Briefly and at the risk of oversimplifying the detailed explanation of the writer in Assessment of Skills, Knows refers to students becoming aware of content knowledge. Knows How refers to knowing the procedure to execute some skill and it includes, “rules, algorithms, tactics, techniques, approaches, manoeuvres or moves” (Leong, 2020). Shows How is the stage where students are able to demonstrate that they are proficient in some skill. The last stage Does is when students are able to use the skill learnt in different contexts effectively to achieve desired outcomes in their real life.

As one example, let us consider, the contrastive conjunction, despite. This is a word with a very powerful function which among other things, is used to imbue arguments or reports with the aim of demonstrating accountability, with persuasive force. It is not uncommon for this word to appear in the Grammar Multiple Choice Question section of Paper 2 at the Upper Primary levels.

Students may first get to Know of the word during a classroom lesson. The next stage is when the student Knows How to use the word in a sentence through being shown examples or demonstration by the teacher. They will get to Show How to use it by answering a multiple-choice question. At this stage, if students get it wrong, they have to go back to the Know How stage. Here, it will be useful for students, with or without a teacher, to reflect on why they got the answer wrong. They will benefit from insight on their specific misconception regarding how the word is used. With such insight either though self-reflection or through feedback, they will now be able to rectify their misconception and practise more Show How. Getting the MCQ right is not the end objective for learning how to use despite. Students will benefit now from using it in different contexts, for instance in their Open-ended comprehension answers to articulate their response succinctly. Beyond exams, they can also practise using the word in real-life conversations and when they are older, in written representations in real world contexts.

When someone is stuck it may be tempting to believe that this is the natural order of things. This however, is not true and improvement is a natural consequence of awareness of needs and targeted attention toward those needs. To illustrate this point, we can refer to two different parts of the aforementioned SEAB publication. The first is another essay by the same writer, titled, Myths about National Examinations. Here, the writer explains that “Force-fitting the examination mark into a bell-curve distribution” is not done. In elaborating, he says the bell curve “describes the distribution of randomly occurring events when nothing intervenes” and that if grades were distributed along a bell curve as believed, “teaching interventions and investments in information technology have not shown up as value”. In other words, according to the relevant authority, the writer, in this case, improvement must be the natural consequence of “interventions”.

In the Preface of the aforementioned SEAB publication, it is stated that “class tests” “are fundamentally AFL, where assessment data generated from formative assessments provides useful information for timely intervention to promote learning”. AFL stands for Assessment For Learning and differs from Assessment Of Learning which is testing for the purposes of determining the ideal environment to ensure optimal learning conditions in the next stage of education. This tells us, that students would need awareness of where they are in relation to their mistakes, in the Miller’s Framework and that with such awareness, they can avail themselves of targeted and timely interventions.

For such awareness, error analysis reports would be useful. Such analysis would reveal if students need to Know, to Know How, or more practice in Show How. In lieu of error analysis reports, students can also rely on self-reflection upon receipt of their marked assignments. During such reflection, they could arrive at conclusions such as, “I was not aware of this previously and I better find out more about this”; “I know this but I am not sure how to use it correctly and I better find out how” and “I know how to do this but at this one stage of the process, I tend to get stuck; I better polish this part of the process through more practice”.

Reflection questions could take the following form, illustrated with the example of ‘Whom” which is tested in Synthesis. Did I know of the word Whom and when it is used? Do I know how to use it in a sentence? Am I using it correctly in this sentence? Which part of my sentence structure is wrong? How can I correct it? Does my corrected sentence look like model examples of how the word is used?

To do what we can’t do, we need to know what we don’t know.

The Brain Dojo