“Internet Gaming Disorder” (IGD) was recently included in the Appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V (DSM-V) and as “Gaming disorder” in the draft of the 11th revision of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).

– What do we know about children and technology? OECD

Important questions for future research relate to … not only the risks but also how media provides opportunities for positive development, such as engaging with friends, forming new peer relations, and experiment with uncertainties or overcoming fears.

– Media use and brain development during adolescence

There is no conclusive evidence that screen time can only lead to bad consequences. Experts do not yet know exactly how much screen time is healthy. Screen time can yield benefits when used in moderation. These and other insights were part of an OECD publication which compiled findings and recommendations based on available evidence on screen use.

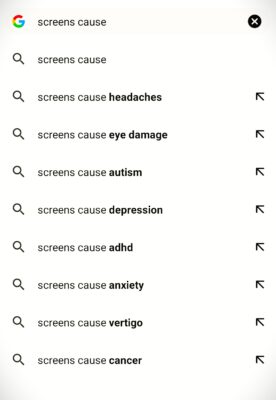

The authors began by saying that much of the current fear over screen use as evidenced by trending search terms on Google, may be unfounded. The recommendations in their publication are premised on the following. Screens are becoming a necessary part of education. Computer games are popular. Indeed, “Hundreds of millions of people spend billions of hours each week playing games” (Brown, 2017; Lanxon, 2017; McGonigal 2011; as cited in Rooij et al., 2018). Content accessed via screens, that is to say, internet or programmed content via television can be beneficial.

Therefore, the authors are of the view that knowing how to engage with screens is important since screens are here to stay.

Though Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) was included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) which “contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria for diagnosing mental disorders”, it was classified “as a condition warranting more clinical research and experience before it might be considered for inclusion in the main book as a formal disorder” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

There is intense ongoing debate between clinicians on whether Internet Gaming Disorder should be designated as a formal clinical diagnosis. There are clinicians who are opposed to such classification. For example, Rooij and a significant number of his colleagues co-authored a response paper arguing why a formal classification is premature and not as of yet, warranted.

In the main, they are of the view that “excessive” gaming could be a coping mechanism which belies other root causes such as depression or anxiety. They ask questions like, if a gaming disorder relates only to “gambling oriented games or to video games more generally”, if it is caused by underlying mental conditions or by “alluring game mechanics” and if it only relates to online gaming or if it also includes offline gaming.

Their main concern regarding inclusion of the classification in the WHO’s ICD-11 is that there is too little evidence that such a condition exists and that we should not be too quick to attach labels because that would have repercussions for many. For example, they pointed out that though it may appear like different published studies conclude that IGD should be classified formally, many of such studies derived their conclusions from the same data set which incidentally happened to be from a study conducted in Singapore in 2011. This Singapore study appeared in the journal Pediatrics and based its findings on a longitudinal study over two years on around 3034 primary and secondary school children in Singapore. It concluded that “depression, anxiety, social phobias, and lower school performance seemed to act as outcomes of pathological gaming” (Gentile et al., 2011).

To be sure, the OECD publication does highlight that mental well-being measured by responses to a life-satisfaction questionnaire, appeared to increase with about an hour of daily screen time. Mental well-being appeared to decrease proportionately with every additional hour of screen time. Those who spent 6-7 hours on the screen daily scored lowest for mental well-being. This led researchers to investigate the Goldilocks zone for screen time – not too long and not too short. The current consensus appears to be that this depends on the individual and that screen time becomes too much if it begins to “displace” other essential activities like homework, socialising, family time and exercise.

In response to concerns over the detrimental effects of excessive gaming, South Korea enacted the Cinderella Law which prohibited anyone below 16 from playing computer games between midnight and 6am, in 2011. (Taylor, 2021). After 10 years or so, the law was repealed in 2021 and South Korea relies now on parents to decide how much their children should game.

Rooij and colleagues (2018) draw a distinction between “high engaged gamers” who may appear to have problems but are in fact very healthy because they retain control over their ability to disengage and pay attention to other aspects of their lives.

Gaming is not altogether bad. The OECD publication gives the example of active games where gamers have to move around. One example of this is Pokémon Go. Active games, for example those which make use of augmented reality may allow for physical exercise. Crone and Konijin (2018) suggest that designers are currently working on games which make use of “biofeedback” to “help youth cope with stress and anxiety” and to “help children cope effectively with anxiety-inducing situations”.

They also suggest that games and “immersive virtual environments” could be designed to train the DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) which is the part of the brain, which controls impulsive behaviour and helps us to be more reflective instead of being purely emotional. They said this in the context of how the DLPFC of adolescents is not fully developed and so they may be more inclined to believe sensational fake news online and how they may experience emotional and self-control issues with too much exposure to certain types of games.

Screen time is not limited to games. It includes, social media use and television viewing. The authors of the OECD publication are of the view, that when used appropriately, both can be beneficial. In the case of social media use, teenagers could feel connected to peers. In the case of television or YouTube, educational content is beneficial. They recommend “co-viewing” in the case of programmed or user-created content so that parents would be able to provide context and guidance. Children can be also guided on what privacy means and how to be empathetic as they participate online. The authors add that children will do what parents do and that parents are in a powerful place of influence over their children’s screen use, by being role models.

They point out that digital skills are essential. They recommend that students can be encouraged to acquire digital skills by spending time online learning to create content in addition to consuming content. For example, some students here are Youtubers in their own right and have significant following.

A world of information is available online and it seems wrong to not take advantage of this. In a New Culture of Learning, Thomas and Brown (2011) make a compelling case for Massively Online Multiplayer games (MMO) by showing how they allow collective wisdom for collective problems to emerge. For example, they write, “very few challenges in World of Warcraft can be solved alone” and “a guild’s success depends on how well its members can synchronise their efforts to solve problems”.

Screens do not cause.

The Brain Dojo