Throughout their daily lives, children encounter some situations in which they feel quite certain about their ability to respond accurately and appropriately and other situations where they feel doubtful that they will be able to respond accurately and appropriately

– I Don’t Want to Pick! Introspection on Uncertainty Supports Early Strategic Behaviour

The mistake we make is to assume since it is logical in hindsight then the better exercise of logic could have got us there in the first place

– Edward De Bono

When Alice went after a rabbit down a hole under a hedge, she fell very slowly and found herself in a long, low hall, with several doors. She walked sadly down the middle but not without first trying every door, only to find them all locked. She did not stay sad very long for she found herself a golden key. Without delay, Alice tried the key at every door. The locks were either too large or the key was too small. Unfatigued, she began trying from the first door again when she stumbled upon another door which had been there all along, a mere fifteen inches high. This time, the key fit.

Most students are often intrepid navigators in virtual worlds such as that of Terra Novus in Roblox but fewer approach terra incognita in other domains with as much zest. Experiments have been done to study how children respond to uncertainty and why they respond in certain ways. Such experiments typically require children to choose between two firm responses (Yes/No, Pink/Blue, etc.) and one uncertainty response (Not sure/ I need help, etc.). Researchers found children as young as four, could monitor uncertainty and choose not to commit when the answer was not immediately obvious, especially when there was no penalty for not committing.

When it is relatively cost free to stay uncommitted or too costly to commit prematurely, procrastination might be an apt strategy. When commitment isn’t costly because of unlimited opportunity such as in non-competitive games, risk is often preferred over caution. There are of course, situations, such as exams, when neither procrastination nor being liberal with risk is a viable option. “I don’t know” isn’t an option either.

Yet students often choose to say “I don’t know” in Vocabulary MCQs for instance, by selecting an option at random. As they grow into adulthood, they would realise that information is seldom and often far from perfect and operating under conditions of uncertainty is the order of the day. It behooves them then, to accept uncertainty as unavoidable and find ways to manage it.

Perhaps, to reflect this reality, exam questions comprise both assessment of learning (AoL) and assessment as learning (AaL). The former tests what has been learnt and the latter entails learning through assessment. AaL requires students to apply what they already know to novel situations, gather feedback and then revise their approach. It is an iterative process to cut through the fog for deeper understanding or learning.

It is possible students throw in the towel sooner than they ought to because they view exam questions as assessment of learning. If they were introduced to the concept of AaL, they might not only grow more tolerant of uncertainty but even fully expect it. This way, “I don’t know” morphs into a legitimate starting point suggestive of strength, from being an end point and an expression of helplessness.

Students say “I don’t know” because to them, knowing means to see the end from the beginning, to apprehend the answer at once (state of knowing). When they understand that knowing is also to see little by little till the end is in sight (process of knowing), they might be less fazed and more empowered in the face of uncertainty. Rather than linger at the threshold, gripped by anxiety, they would be more willing to take small steps forward to establish the lay of the land. This type of knowing is in fact more commonplace in the real world with all its complexity and dynamism.

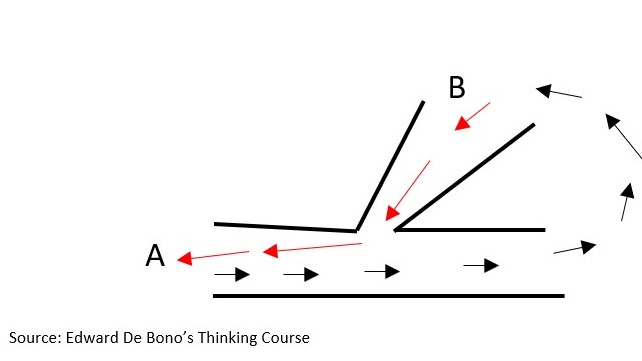

One reason why students may be hesitant toward an exploratory approach is the view that it is somehow inferior to the state of knowing. To understand this mentality, the following diagram is useful:

Point A represents a problem and Point B represents its solution. The path taken to reach B is represented by black arrows. Once a solution, B, has been reached, a shorter route, represented by red arrows, from B to A becomes visible on hindsight. Students often look for a direct route from A to B and when none is visible, they might lament their lack of ability. When the answer is revealed to them, they conclude that it had been staring them in the face all along and that they should have known better.

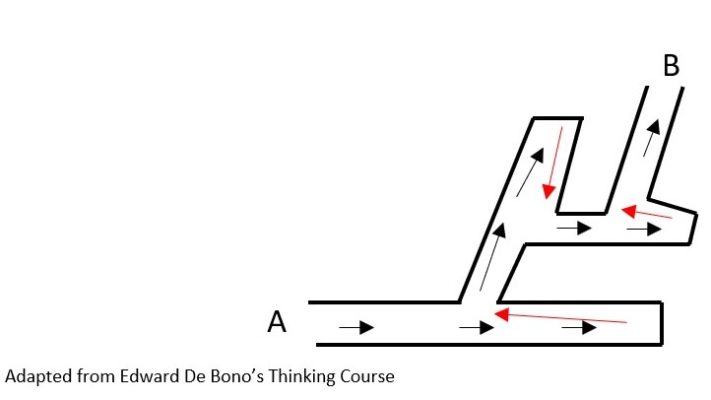

They might feel less pessimistic, if they were told the only way to reach B is to take a circuitous route and learn through trial and error. Most times, the process of reaching a solution looks like this:

As can be seen in this diagram, in the absence of an odd shaped periscope, it would be impossible to have sight of B from A. While there are thinking processes akin to mental periscopes, these often lead to solutions to problems other than A. This is how Post-it notes and penicillin came to be. To reach B, we need the red arrows, the process of backtracking and taking a different route from time to time.

The process of knowing in an environment of uncertainty may be fraught with pitfalls and dead ends. It is far from perfect but perfection does not exist on earth. Even so, we are not entirely without recourse. In a situation of imperfect information, processes such as trial and error are good practice.

Alice opens the tiny door with the golden key and crawls through a tunnel. She catches sight of a magnificent garden on the other side. However, the opening is too narrow and she has to return to where she first began.

As you already know, the story doesn’t end there.

The Brain Dojo