The results provide clear evidence of text structure, sentence structure, and vocabulary as dimensions of writing associated with the authorial aspect of writing. Similarly, spelling, punctuation, and handwriting are associated with the secretarial aspects of writing.

– Assessing early writing: a six‑factor model to inform assessment and teaching

One unintended consequence of the change of format is the use of formulaic templates to fulfil the requirement of writing purposefully… where the student repeats the topic in his composition numerously to keep to the ‘formula’ of staying on topic.

– What to Value in Students’ Writing at the Primary Levels

Dog for sale: Eats anything and is fond of children. Should anything strike us as odd in this? Grammatically, there isn’t. Put another way, this arrangement of words is allowed. Since it is in the right grammatical order, users of English worldwide will understand what is meant. And many might laugh precisely because of this very arrangement.

The ordering of words can be grammatical or allowed and yet make no sense. One famous example mentioned in previous articles, was given by Noam Chomsky who is among many other things, a linguist; Colourless green ideas sleep furiously. The word class order here is as follows: adjective, adjective, noun, verb, adverb. A sentence with the same word class order but which would make sense would be as follows: Small, agile creatures move quickly.

The ordering of words must be both grammatical and make sense. Proficient or skilful writers would also be able to order words in a manner that is impactful. Beginning writers would be learning to order words in a grammatical and meaningful way. Proficient writers can be challenged and guided to re-consider how they arrange words at the sentence level to vary impact on readers.

Ordering must also be considered at the level of the whole text which could be a composition or in the case of Situational Writing, a letter.

In a recent paper which appeared in the journal, Educational Research for Policy and Practice, Ordering featured prominently among four other areas which students learning writing need to master. The other areas were, vocabulary, spelling, punctuation and handwriting.

The authors were minded to test the Writing Analysis Tool developed by Noella Mackenzie. This tool lists the aforementioned 6 areas. They concluded their paper with the confirmation that this tool is valid – these are indeed the areas students need to pay attention to; and with suggestions on how to help beginning, developing and proficient writers.

After collecting writing samples from 1799 children aged 6-7 (Year 1) from 75 schools in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia, the three researchers, Scull, Mackenzie and Bowles (2020) chose 250 samples such that children from the two genders, different SES groups as well as cultural and linguistic backgrounds were adequately represented.

The children were asked to write for twenty minutes on “anything they liked”. No prompts were given.

Before, we proceed to discuss their findings, one interesting observation in their study was that there was no clear and persisting difference between how girls and boys performed. There was also no strong indication that SES impacted performance in a significant way.

Strong performers got rated highly on all 6 dimensions. The rating scale ranged from 1-6. For example, for the dimension, Sentence structure and Grammatical Features, a 6 rating would require “a variety of sentence structures, sentence length…a range of sentence beginnings…sentence flow with sequence throughout the text and show a consistent use of tense”. In contrast, a 2 rating for this dimension would have been given if the student, “shows an awareness of correct sentence parts including noun/verb agreement.” However, the “meaning may be unclear”.

It was found that strong performers paid more attention to organisation at the sentence and text levels and word choices. They paid less attention to spelling, punctuation and handwriting. In other words, their handwriting may not have been neat and their spelling may not have been always correct but by and large they were able to string together a highly readable and complex composition. One way of looking at this would be that this group was more concerned with what they wanted to communicate than how to be correct. The researchers attributed the spelling and punctuation errors of this group to “inattention”.

The average performers also paid more attention to ordering of sentences, paragraphs and vocabulary. However, the researchers were of the view that their spelling, punctuation errors and the way they put words, sentences and paragraphs together showed that they needed more awareness and training in these areas.

The researchers recommend that students who are unable to fulfil task requirements should be given “careful teaching” on all 6 dimensions. They were careful to point out though that these dimensions should to the extent possible be taught together and not in an isolated way.

This research suggests that if the student is already able to use vocabulary appropriately and is able to string words and paragraphs together, focus of guidance should be on the depth and impact of writing. When the student is unable to put words in a meaningful order or finds spelling and word choices obstacles to expression, a more structured and segmental (not overly) approach is required, before depth and impact can be addressed.

Teng (2018), who contributed an essay on writing in Singapore classrooms, to a Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board publication, suggests that proficient writers – writers who are by and large able to spell, punctuate and order would be better placed to deal with theme based-writing such as that which is required at the PSLE.

She suggests that “intermediate” writers would require more scaffolding to become familiar with personal recount and narrative structures.

Finally for students who may find theme-based writing daunting because of the various competencies required, Teng (2018) recommends the “Personal-Appeal approach”. In essence, to foster interest in writing and motivation to write, these students could be asked to express themselves through “free-writing”. Examples of this include, “diary entry” and “response to a news article”.

Teng (2018) provided an insightful and noteworthy clarification on the Continuous Writing task. Students are not limited to narratives or stories. They are allowed to write expositions as well. This might be game changing for some students. This would impact how students structure their writing.

Both Scull, Mackenzie and Bowles (2020) and Teng (2018) emphasise that writing is about meaningful expression which takes into account, both what is being communicated and to whom it is being communicated. As mentioned elsewhere, if composition writing was taught this way, instead of as a strict formula to follow, students might begin to realise the power they have to communicate.

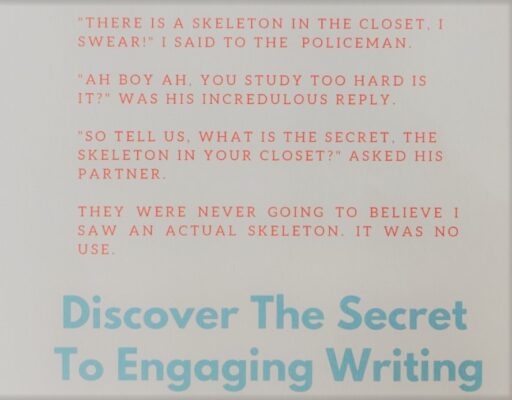

Good writers can make skeletons come alive.

The Brain Dojo