… children need to know prepositions, but gradually learning all the different meanings including their figurative senses, becoming aware of the connections that exist among them.

– An Analysis of Prepositions in EFL Textbooks in Primary Education

I have been staring at them as I have been writing these words not noticing them or seeing them there, right in front of me: staring through them, beyond them, except them.

-‘Tissue of making’ in practice-led research: Practi-care, prepositional thinking and a grammar of creativity

It might be considered remiss to conduct an entire lesson on prepositions at the Primary 6 level and beyond. At higher levels, there is a greater degree of abstraction in content and there is an expectation that lessons would cover more advanced skills such as how to write persuasively or creatively. Prepositions are considered basic and straightforward.

The British Council says otherwise, describing them as “tricky little beasts” which role in the “overall scheme of things” is often misplaced and that we ought to “give them more time in the classroom than is usually the case”.

Prepositions are tricky because of a quality of language termed polysemy – the association of one word with two or more distinct meanings (Nordquist, 2019). The British Council suggests that there are “as many as 18 different functions” for the word “at”. Students are explicitly taught only the basic functions which relate to an object’s location in space – I am at the foot of the hill and direction of movement – Coming at me. In a listening comprehension exercise, students would be able to choose the corresponding picture to such preposition use in an audio recording. This is the basic use of prepositions.

At higher levels of abstraction, even tertiary students have been found to make prepositional errors. For example, Lee, Yoo & Shin (2019) documented that a group of Korean university students lacked “variety” in preposition use suggesting that they “lack knowledge of alternative expressions with similar functions” (Salazar, 2014 as cited in Lee et al., 2019). The tertiary students had also made errors of omission – where a required preposition was dropped and errors of misuse – where an inappropriate preposition was used.

Apart from syntax which in and of itself is a good reason why it is worthwhile to dwell on prepositions – does ‘by’ in ‘by x date’ include x? it might be surprising to some that something deemed basic is the very substance of creativity.

Francesca Rendle-Short is an award-winning novelist who also teaches writing at RMIT Australia. She exhorts us to turn to prepositions for perspective and nuance. She says there is “value in thinking prepositionally”; that prepositions are the very tissue of literary creations.

She demonstrated prepositional thinking when writing about her relationship with her father. To generate content for her essay, prepositional thinking helped her think not just about her father but also, “into, through, away from my father”. Each of these prepositions when considered would shine a light on different aspects of the relationship.

Prepositional thinking, according to her is, “a way of processing … thinking through thought and language, how thinking patterns itself, the self-talk, self-noticing, the inter-personal awkwardness that comes with it, and how one might map out the relations…”.

For example, she asks how close one has to be to be near. She says the prepositions around and between would each offer a valuable lens with which relations with an issue, event or person can be analysed.

Indeed, this is the function of prepositions – “as vital markers to the structure of a sentence; they mark special relationships between persons, objects, and locations” (British Council).

Here of course, the ordinary understanding of the definition is in relation to sentences. As creative types tend to, Francesca thought laterally and exported this understanding to another domain; of real relationships.

Typically, we contemplate a state of affairs before committing to a preposition on paper – into thin air. This is vertical thinking – “one moves in a clearly defined direction towards the solution to a problem” (Bono, 1970). Prepositional thinking is to do things in the reverse order. One thinks of a preposition and then contemplates the state of affairs in relation to the preposition. In this way, prepositions, “provoke a different way of looking at the situation” (Bono, 1970) which is a hallmark of lateral thinking. For example, let’s say the computer crashes and an important document disappears into thin air. Thinking about the preposition, ‘from’ might inspire creation from thin air.

When we think of creativity, we think of the creation and how it is so unique and how it is so praiseworthy because it is different. When we are told that to be different, we have to return to the fundamentals for reinterpretation or repatterning, we get concerned because – what if I am marked wrong? or I already know this? Tell me something more advanced. Where are the hard words which I can use to impress?

There is a difference between something basic and something which can be used in a basic way. There is nothing altogether and only basic about any element of language because a limited number of characters or letters have to be used to generate an unlimited number of possible meanings.

So, every element including, the small ones such as prepositions has to be respected for its generative capacity like an “omnipotent” cell which has the ability to “divide, differentiate and develop” (4 Types of Tissue, Oregon State University) new meaning. This is all the more so for prepositions which are a “closed class” which form a “a select group of words that don’t accept new members to their club” (Simpson, 2014) unlike nouns or adjectives.

Language follows a nested structure which means that a preceding word will constrain the possible options for a word in a sentence. The sentence Good of off primly the a the the why (Lycan, Philosophy of Language) is not intelligible because it offends both paradigmatic and syntagmatic rules. The word the should and could never appear before the word a. Also, this sentence does not convey meaning. So, there is a boundary beyond which meaning would fall away.

This could be why there is a lot of concern in being right and being marked wrong. However, creativity does not mean utter disregard for rules. It entails instead possible reinterpretations which would lead to refreshing results while preserving intelligibility.

Thurner and others (2015) writing for The Royal Society, say “Sometimes words can act as a linguistic hinge, meaning that it allows for many more consecutive words than were available for its preceding word” and they remind us that being flexible allows for “a degree of ambiguity in the linguistic code and is one of the sources of great versatility”. Tobin (2008) says prepositions are notorious for their multiplicity of meanings because of Zipf’s law – “the smaller a form, the more frequently it will be used, and the more meanings and functions it will have attributed to it”. Whether or not this is because of Zipf’s law, the substantive proposition about small forms seems intuitive.

This is not unlike some systems of divination in which answers to every question pertaining to each and every conceivable; from the minute to the grand aspects of life are contained in a very limited set of couplets.

Basic use of prepositions is taught at lower levels. Focus on prepositions tapers off at higher levels though prepositions are integral especially in complex constructions. Prepositions are also useful for creative writing.

How should students be taught to use prepositions in complex constructions or abstract formulations?

Hung, Vien and Vu (2018) suggest that conventional textbook ways of rule memorisation “do not help students learn and enhance their achievements in English prepositions successfully” especially for students who speak a different first language and cite the example of Japanese English learners who did not improve much after such treatment.

They instead recommend cognitive linguistics which in essence is to use existing mental structures in service of integrating new knowledge. They suggest that “teaching prepositions should be meaning-based and employ image schemas”. Their pedagogy is based on two theories; Domain Mapping Theory and Theory of Conceptual Metaphors.

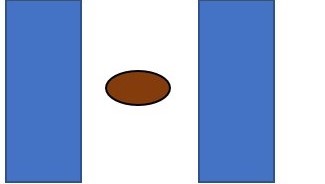

It sounds complex but is actually not so. It entails using a sentence with a target preposition, a corresponding photograph which shows an image of the sentence and the use of basic shapes to abstract the principle of the preposition from the photograph.

Let’s say we want to teach the abstract use of the word “between”. We can use the sentence, The sign is between the river and the path. The principle in abstract form would look like this:

The sentence is represented in the photograph which is featured at the beginning of this article. This however, is using “between” in a basic, concrete way. The abstraction in the form of the rectangles (representing the river and the path) and the oval (representing the sign) would help students map what they know in the concrete form (as shown in the photograph) to metaphorical forms. A metaphor according to Lycan (2018) is “figurative” and refers to some “similarity” between two entities which are not usually found in the same domain.

Students who internalise this abstraction would then see that “between” separates two entities in the physical domain. They would be able to map this understanding to other domains which are not spatial such as relationships.

It may be time to reconnect with tricky little beasts.

The Brain Dojo