semiotic economy… based around codes, signs and symbols—where the lion’s share of productive work and consumption, lifestyle and community is based on linguistic and communicative competence, information and capital flows, engagement with new media and technologies

– Towards Research Based Innovation and Reform: Singapore Schooling in Transition

First of all, the character for shinobi consists of ‘blade’ and ‘heart’

– The Bansenshukai

The one language skill that is crucial and has not received much attention in formal education systems is translation. We leave translation to the experts. Translation is difficult for a number of reasons. It requires a certain level of competence in the source and target languages. Knowing vocabulary and grammar is not enough. It is time consuming.

The purposes of learning English can be broadly classified into two categories. The first is its functional purpose, that is, to be able to communicate. The second is its aesthetic purpose, that is, to be able to appreciate. Translation is a skill that would fulfil both categories. It is also a very powerful metaphor for learning and guiding behaviour.

Without basic awareness of how a language system works, it will be difficult to appreciate its creative use or to critically analyse its information or truth value. So, in primary school, the final English exam is designed to test competence in grammar and vocabulary in and of themselves and in an applied fashion, through open-ended comprehensions, situational writing, compositions and stimulus-based conversation. At higher levels, students are introduced to literature and persuasive texts for appreciation and critical evaluation.

This skills-based curriculum would develop capability to understand the news, advertisements, write reports, have conversations and make presentations. These are the bulk of what is required for daily living and work.

Accordingly, so far, students are tested only on producing narratives, expositions and understanding of texts, in written and oral forms. Translation is not taught and tested.

This is a functional approach to teaching and learning language and is based on looking at what is required at present and some assessment of what might be required down the road. Such assessments are usually based on an extrapolation of current trends. Primarily, the idea is to equip a student to plug in to the world around him. So far, the value of translation in the wider world may not have been apparent and so there has been little focus on it.

The current thinking about learning more than one language is that it allows market access. The other reason is that it allows preservation and development of cultural roots. In effect, the languages are learnt in parallel tracks and thought of as modus operandi in entirely different worlds. The relevant and currently endorsed concept in this mode of thinking is that of code switching. Different languages are used in different domains.

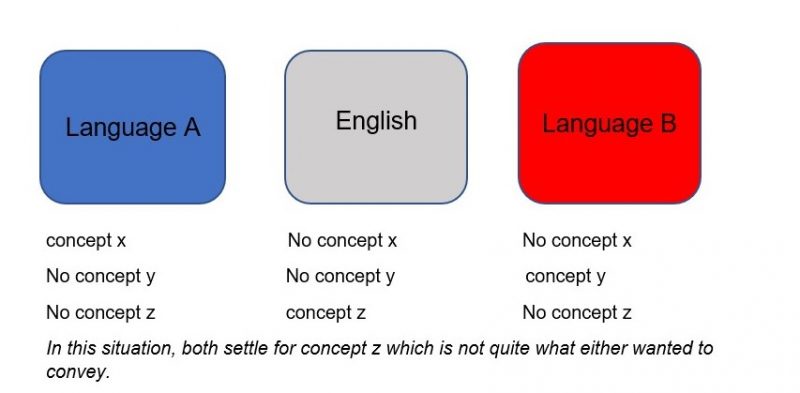

There is untapped synergistic potential for bilinguals or multilinguals. Consider a negotiation with parties who speak a different native tongue. A monolingual would be at the mercy of an interpreter who may have his own biases and interests or be not sufficiently familiar with context. A bilingual is slightly better off, he would be able to converse in the other’s tongue. This is still not satisfactory because he is at a disadvantage. Using a bridge language appears to be the best solution because it does not prejudice any party. However, a bridge language as it is currently thought of could well leave both parties worse off because they are more articulate in their native tongues.

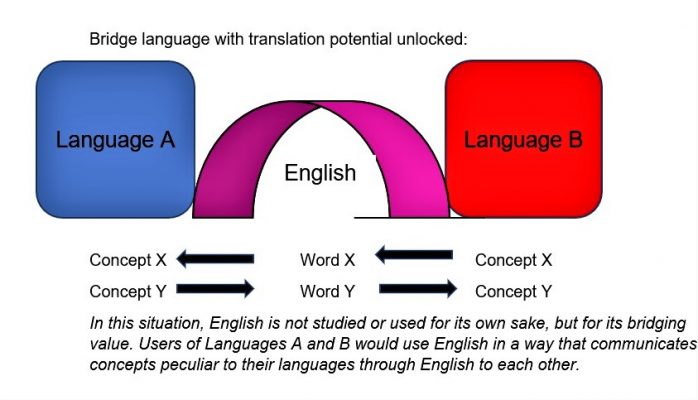

If A feels inadequate in relation to B, A would guard against B. This does not facilitate cooperation. If A and B have a bridge language, they might feel assured by its neutrality but still feel frustrated because they are both grasping at what the other means. Imagine if A knew how to convey exactly what he wants B to understand in a bridge language. This would entail using the bridge language in a way which approaches equivalence in the other’s language. So, the relevant concept is not lowest common denominator but conversion. Another game changer would be if A is able to communicate concepts of A’s native tongue, in the bridge language in a way that would allow B to think about such concepts in his own tongue. Then the parties would truly see eye to eye.

Consider the word or pragmatic particle, lah. When No lah is uttered and the lah is dragged out, there is a very specific meaning intended. In a formal system, the use of lah would be discouraged because others may not understand. Yet, it is very effective in its role as social lubricant.

When someone says, No lah, it means this person is trying to downplay something so that the hearer would not feel envy or think the worse of the speaker. In a situation which requires a No Lah, but which occurs in the context of conversing with a non-local who could not be expected to understand the dialect, one is precluded from having recourse to such an effective tool.

Someone who thinks in terms of translation would be able to harness the power of No lah in the bridge language, let’s say standard English, in a way that the hearer would be able to receive in his own language. A simple non-imaginative way of doing this would be to say, “Not at all” or “Far from it” coupled with “Don’t think of me this way” and an appropriate facial expression. To do this, one has to think of what the peculiar utterance in the native language achieves, and how to achieve that same effect in the bridge language as it is understood by the non-native hearer.

To know how it will be understood by the non-native hearer, a knowledge of his language would be necessary. Students in a bilingual system would be able to do this. They learn two languages. Instead of merely speaking two different languages in different situations, they could focus on how to represent a term or concept of one language in another. This way, when they deal with non-natives, they would be able to have greater reach.

The following diagram is provided to aid visualisation of thinking in terms of conversion vis-a-vis lowest common denominator.

Bridge Language, English, as it is currently used:

This translation approach to learning English is in line with the multiliteracies model of the New London Group which is currently being quite seriously considered in mainstream schools.

Multiliteracies in essence states that a few assumptions underpinning the traditional language teaching model no longer hold. In the traditional model, there was a standard grammar and standard conventions. There was right and wrong. Also, media was monomodal – text only or speech only.

Cope and Kalantzis (2008) of the New London Group explain that the reason we used to get information from words only is because in the past, the, “elementary modular unit in the manufacture of traditional pages was the character ‘type’ of Gutenberg’s printing press” and that printing pictures was expensive. This has changed because now, the elementary modular unit is the “pixel, the same unit from which images are rendered. The pixel is easily available through present day ICT.

According to them, this is why representations are increasingly multimodal; a mixture of text, visuals and audio. They question why schools are still quite heavily focused on traditional conventions and right and wrong when the communication landscape has changed so much.

Multiliteracies is not merely multimodal but also comprises a new way of making meaning. One way to make new meaning is through a mixture of text, visuals and audio. It is not the only way. The multiliteracy pedagogy comprises, “redesigning” (Kope & Katlantzis, 2008) new representations of meaning from “available designs” which are existing conventions.

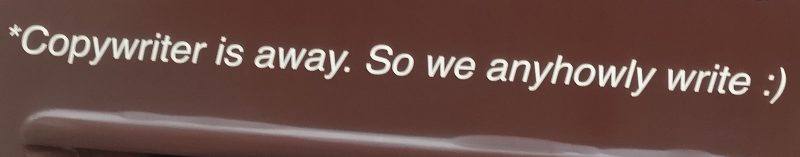

This is an example of redesign:

The last line of an advertisement at the back of a bus. It goes against conventions but is very effective in its purpose for that very reason.

The New London Group have championed the redesign of English language pedagogy to allow for more flexibility and experimentation with language. They suggest this can be achieved with “synaesthesia” which is “the process of shifting between modes and re-representing the same thing from one mode to another”.

The modes they had in mind was video, audio, pictures and text. Multiliteracies interpreted another way could be a literacy arising from different literacies. We do this with children sometimes. To help very young children understand, we reword adult language in a way that would make sense to them.

Miscommunication is a huge problem even when things have been stated plainly in writing. If we think of language not as a standard form which is understood the same way by everyone but as primarily a means of translation, miscommunication can be reduced and communication potential can be enhanced. This means first recognising that no two people use language the exact same way and that skilful communication requires translation into a form coherent to the receiver.

As a skill, translation is very useful. We could access great works and opportunities in other languages. As a metaphor, translation is powerful. If we thought of ourselves as translators and practised translation in everything that we did, we would ask ourselves how we can translate what we encounter in one domain to applicable learning in another. This would multiply creative potential.

English and indeed standard forms of any language have been over-promoted for their potential to bridge different realities. This has given a false sense of confidence.

If two converse in some standard form, what they see is the language and not each other. Seeing to appreciate is possible at a distance; seeing to understand is not. We need to cross that bridge.

The Brain Dojo