If you write with a goose quill you scratch the sweaty pages and keep stopping to dip for ink. Your thoughts go too fast for your aching wrist. If you type, the letters cluster together, and again you must go at the pokey pace of the mechanism, not the speed of your synapses.

– Foucault’s Pendulum

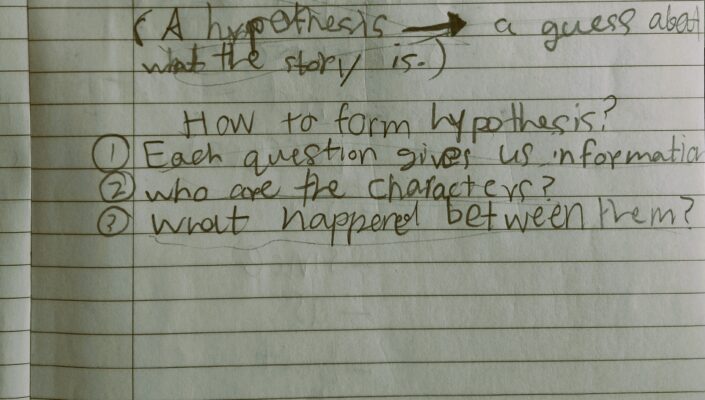

The more deeply information is processed during note taking, the greater the encoding benefits.

– The Pen is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking

A recent Today Online article discussing Tik Tok, cited Mr John Shepherd Lim of the Singapore Counselling Centre as saying that the continuous supply of entertaining content and the “rapid-fire nature” of its videos might lead to a shortened attention span and a judgemental attitude. It is not uncommon to see students engrossed in short YouTube videos.

Learning devices and mobile phones are now widely used. This may have changed the way students prefer to learn. Could it be that students prefer watching to reading and typing to writing, given the former in both cases are taxing and the latter in both cases appear to fulfil the same function? For the most part, learning devices and mobile phones have been a boon to learning.

Videos on YouTube and posts on Instagram do undoubtedly carry educational value. The assumption behind the brevity in short-form videos or posts is a shortened attention span. The attention span could be shorter for two reasons. First, there is so much to read or watch and accordingly the proportion of time given to each standalone video or post is less. Second, the ability to sustain attention itself could have become somewhat reduced because of the interaction with short-form videos and posts.

Getting used to a steady diet of short-form videos or posts could lead to an aversion to words or more precisely to paragraphs of words. Even if we have not reached a stage which can be properly characterised as aversion, perhaps we might be more inclined to agree a little more readily, that there may now be a preference to video or hybrid content (video and text or pictures and text) over linear, text only content. One reason for this could be because multi-modal and video content are more engaging in their own right. Another reason could be because reading long text can be mentally taxing in relation to consuming other forms of content.

While students can learn to comprehend and produce multi-modal content because such content does encode or communicate information more efficiently and perhaps effectively, text remains crucial to the encoding and communication of information.

In most endeavours, there are both theoretical and practical aspects. While videos are great for practical aspects, the theory is often found in long text form. Without theory, it will be difficult to master the practice. While there are movies of books which are popular, the book version is usually a lot richer in detail and nuance.

The availability of learning devices and mobile phones could lead to reduced motivation to take notes by hand because this is also taxing.

Is it true that students may now prefer watching videos to reading longer texts and typing to writing notes (if and when they do)? Given the wide availability of learning devices, there has been research which observes that students, when they do take notes, prefer typing to writing them.

Having discussed the importance of sustaining attention beyond 280 characters, we can now turn to the question of notes.

Are they of any use and does it make a difference whether they are written or typed?

There has been much research which supports the proposition that note taking enhances learning and exam performance. There are many ways to take notes. These include, the Concept Mapping method (mind mapping), Cornell Method, Matrix/ Charting Method and Outline Method (Savitri et al., 2019).

Students can take notes during different occasions of learning. They could take notes when listening to an explanation in class, reading longer texts such as that found in a textbook or when attempting to answer questions based on a text.

Though it might appear like in primary school, subjects like Science lend themselves more to note taking and subjects like Math or English are more practice-based, note taking is essential across subjects.

Let’s take primary school English. One of the most useful ways to take notes is to record mistakes made during practice along with the correct answer with an explanation why an answer was wrong and why the correct answer is what it is. Students, even adults have trouble sometimes with using the right preposition in phrases. Students could record prepositional phrases which are new to them each time they come across such phrases. Annotation if done the right way, may also be useful when attempting open-ended comprehension.

Some students do take notes. However, they may not be doing it the right way. When younger students take notes, they do so in two main ways. First, they copy what is written on the board. Second, they may write word-for-word what they hear in class. The second way is known as “verbatim” note taking (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014).

Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) wanted to find out if typing notes was as effective as writing them and if taking notes verbatim was as effective as taking notes after some individualised processing. They conducted three tests with students under slightly different conditions.

They found the following. Students who wrote notes by hand wrote far fewer words than those who typed. Handwritten notes were far less word for word (verbatim).

In each of the three tests mentioned above, students had to watch some content and write notes at the same time. In two tests, they were tested on their knowledge of the presented content after a short delay. In the third test, they were given a week alone with the notes along with ten minutes to study before the test. In these tests, there were factual recall questions as well as conceptual questions which tested understanding.

When it came to sitting for the test shortly after watching a video, students who wrote their notes by hand performed better than those who typed their notes especially when it came to conceptual questions. It was found that students who typed their notes had a lot more verbatim content and that those with a lot more verbatim content did worse.

Researchers then thought perhaps if they told the students who typed their notes not to take notes in a verbatim form, they may perform as well as those who wrote their notes by hand. They found that even after being told that they did not have to transcribe (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014), students with a laptop continued to take notes in a verbatim fashion and that this led to relatively poor performance.

When it came to the test which was taken a week after watching presented content, those who hand-wrote their notes and studied them did significantly better in conceptual questions.

Researchers point out that note-taking benefits learning in two ways. First, taking notes in a mindful way, that is to select relevant information from what is being presented, paraphrasing it (Savitri et al., 2019) and organising it in a way which makes sense helps students understand better. Second, revising such notes helps bring to mind whatever was learnt in the past, reinforcing learning.

Mueller and Oppenheimer (2019) suggested that students who typed their notes may have had trouble understanding the content in their notes while they were studying because at the time they typed the notes, they may have been more focused on getting the words right rather than spending time wrestling with what was being taught.

This suggests that hand-writing notes in a paraphrased way and studying such notes would lead to better learning and exam performance especially in questions which require more than mere recall.

Not everything noticeable is notable.

The Brain Dojo