Social studies is also a content area grounded in natural learning processes. Much of the material is derived from basic, societal observations. It is a content area that reflects the world it exists within, creating a powerful experience for the students who partake.

– Influencing Middle Schools Students’ Perspective of Media Literacy

The passive mode takes place when learners receive information without engaging in any overt behaviour related to learning…

– Eight Ways to Promote Generative Learning

Learning English is not only for comprehension and creation of texts but also to be able to think in a logical way in order to come to a reasoned conclusion and to participate meaningfully in issues which matter. Proficient students may be able to phrase answers to a text correctly in which the presented facts are incorrect.

English language classes lend themselves to critical thinking guidance because students would be exposed to various texts written with various perspectives and objectives. It would seem a waste to focus on technical aspects of language with a view to sharpening technical competence only when they can also be engaged in meaningful conversations on substantive content.

One objective of text selection in classes could be the transmission of values. Texts which fulfil this objective could include articles valorising individuals whose stories are the exemplification of desirable qualities. Questions set on such texts typically do not lend themselves to questioning of the truth or the lack thereof of presented content. Texts could also be selected purposefully so that students recognise that every writer is a person with self-selected objectives and values. Such selection would empower students to realise that they go through education not merely to receive a presented world-view but to make sense of it through everything else they know to be true.

This is important because someone who swallows hook, line and sinker what is being presented may find themselves swayed easily when another more eloquent presenter offers a compelling counter-narrative. It is through thinking critically that trust can be fostered – I have formed my own questions; my objective is less to regurgitate than to arrive at the truth which would lead to right outcomes and I have had my questions answered to satisfaction.

Learning how to engage critically with texts will become more relevant the more students become proficient in English and begin to realise they can self-select reading material. It is not enough for students to merely comprehend. They need to be able to evaluate for truth value and relevance – something true may only be true in a particular context.

Learning can be structured and formal learning with others in a classroom, or self-directed and less formal. To enable students to become less susceptible to eloquence, charisma and mastery over forms of delivery simpliciter, an understanding of the different types of learning and ways to learn better is necessary.

In this regard, Fiorella and Mayer (2015) introduce the concept of “generative learning”. Generative learning can be said to occur when students are able to “actively make sense of to-be-learned information during learning—by selecting the most relevant information, organizing it into a coherent mental representation, and integrating it with their existing knowledge”.

They highlight the difference between reproductive and productive thinking (Katona, 1940; Wertheimer 1959 as cited in Fiorella and Mayer (2015). Put somewhat crudely, in the former model of education, a good student is one who is able to repeat and, in the latter, a good student is the one who is able to build upon, contextualise, apply and offer a counter-narrative where fitting. Students would need generative learning to think productively.

For example, consider the No sooner had … than structure, tested in the Synthesis component of the Language Use paper. A sentence which begins with hardly, barely, scarcely follows the exact same structure except that unlike No sooner had… the word when is used as connector in place of than. There are two ways to get such questions correct in exams. The first is to learn it with a reproductive mindset – No sooner had is paired with than and everything else is paired with when. This imposes a load on memory. Students would have to remember structure in a formulaic way. Students do make mistakes when they learn this way because they may remember wrongly. The other way is to learn how the purpose of the No sooner had construction differs from that of other constructions which may at first glance appear very similar.

Fiorella and Meyer (2015) also explain that generative thinking is necessary for students to move up the interactive-constructive- active-passive (ICAP) framework (Chi, 2009; Chi & Wylie, 2014 as cited in Fiorella & Meyer, 2015).

Students are passive when they receive from a chalk and talk channel. All trained teachers know that what is taught and what is understood can be worlds apart and that children may often not be able to estimate their learning accurately (Dunlosky and Lipko 2007; Lin and Zabrucky, 1998 as cited in Fiorella & Meyer, 2015). It becomes important then to be able to verify what each student has understood in demonstrable ways and this would require more than brief engagements either to answer a question a student has or to have a student answer a question posed by a teacher.

Students are active when they record what they hear in the form of notes. This per se may not lead to learning and serves only as a memory aid for more meaningful processing at a later time.

They are constructive when they can go beyond merely repeating what is transmitted. Here students might be able to apply what they have learnt in a manner which shows they have internalised transmitted content. There should be ample opportunity for on-time feedback which requires a student do- teacher guides and/or corrects- student corrects format.

Students enter the interactive phase when they are able to engage in a meaningful conversation, clarifying, verifying, counter-proposing and persuading or agreeing after having had ample time to reason on the content of a lesson.

Fiorella and Meyer (2015) suggest eight tested ways for students to engage in generative learning in and out of class. These eight ways are Summarizing, Mapping, Drawing, Imagining, Self-testing, Self-explaining, Teaching Peers and Enacting.

They qualify these eight ways by highlighting that they may be more effective for students who have less background knowledge on a given theme.

Each of the above-mentioned ways of learning better are not without limitations and have more relevance in certain contexts. For example, Fiorella and Meyer (2015) explain that there are different types of Mapping – Concept Map, Knowledge Map for “part of, type of, leads to” connections between concepts and Graphic Organisers – for hierarchy of relations, “compare-and-contrast” or “cause-and-effect” structures. Self-testing is another example of a learning strategy which works better in certain conditions for certain students.

Four of these ways, Mapping, Drawing, Imagining and Enacting require students to “select the most relevant information for inclusion in the new representation” and the other four “active use of one’s prior knowledge to restructure the material into a more meaningful representation” (Fiorella & Meyer, 2015).

When reading, it is important to tell apart the legs from the limbs.

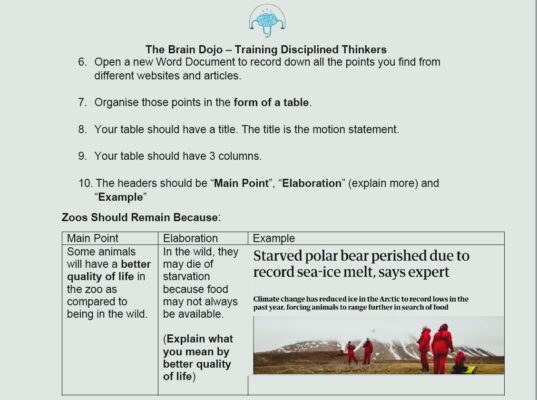

The Brain Dojo