Given this variability in people’s ability to judge the state of their knowledge, the task of future researchers should be to identify the conditions under which people know what they know and the conditions under which they do not.

– On the Genesis of Confidence

I am learning how not to drown so much in the whirlpool of mental activity, and to find some space behind it all.

– A Monk’s Guide to Happiness in the 21st Century

What did Osano of Fools Die and Gail Wynand of The Fountainhead have in common? Both did not believe in unconditionality. They wanted what psychologists say everybody wants; acceptance untied to what they brought to the table. At the same time, they did everything they could to prove to themselves, such a thing could not exist.

To this end, they tested people for fitness and paradoxically, were only at ease when those they tested failed the test. All was then well since the tested had behaved predictably; that is, in a way which fit well with their mental representation of the world.

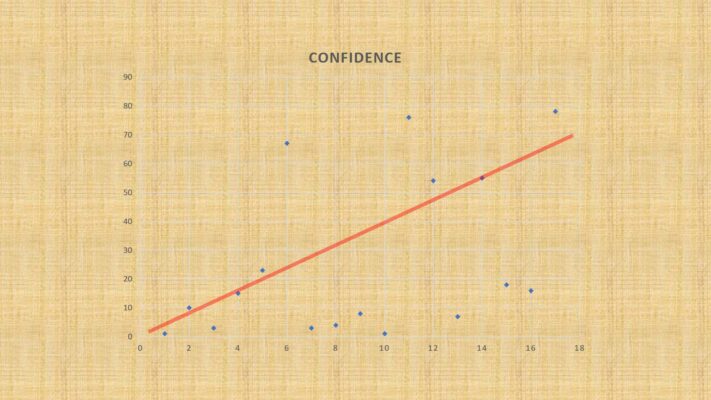

Tests are important for various reasons. They are also problematic for various reasons. One reason tests are important is that they help us increase confidence and reduce what researchers have pointed out to be a mismatch between confidence in a belief and the accuracy of that belief.

Some researchers have said that testing is a biological and survival imperative. Accordingly, these researchers have advised that even if one recognises a test, calling it out would be of no assistance to the tested. Doing so interferes with the backend computational processes of the tester and is likely to cause frustration. Accordingly, the best advice for the tested is that the only way out is through.

Tests are also problematic. They need to be valid indicators of the tested quality. There needs to be sufficient data to establish the presence or absence of a quality. Also, it is not difficult to game tests by studying to the tests or showing the examiner what the rubrics say are indicators of quality. For example, the show Law-Abiding Citizen shows how this may be done.

This is the problem. We need an accurate representation of affairs so that we can make decisions. We never have enough data. At best we can make predictions about how something will turn out. We need to be confident about such predictions to make decisions. It turns out that it is easy to be overconfident and that it is almost always the case that we can be very confident about something which is not true.

What is confidence and what is its relevance? What is its relationship with accuracy? At first glance, it might seem like the two must have a direct connection. For example, a basketball player needs to be confident in his abilities to be able to throw the ball accurately. This however, is not the type of confidence or accuracy we are interested in here.

The confidence spoken about here is a degree of certainty about the nature of something or someone. Accuracy here refers to how closely a perception held with confidence adheres to the reality of the situation or the real person. Some believe that if someone is very confident in his belief, he is likely to be accurate in that belief. In this sense there is a perceived connection between confidence and accuracy.

In actual fact though, there is no such connection.

Indeed, the extent of confidence necessary should be directly proportional to how uncertain a situation is. If the assessment of a situation is a hundred percent accurate, there is no need for confidence. According to an online dictionary, confidence comes from the Latin word, confidere which means have full trust. Why is trust necessary?

Confidence has to do with the following factors: Richness of mental representations and judgement fluency (Gill, Swann & Silvera, 1998). This research may be a little dated but makes a lot of sense and has been cited even at least as recently as 2005.

According to Gill, Swann and Silvera (1998), how confident we are turns on how richly something or someone is represented in our minds. Something is richly represented if there is a lot of information which seems to confirm or corroborate our predictions about it. Such information has to be integrated. This means logical links between the different things which are observed, must be present, to form a coherent narrative.

In other words, let’s say for something to be true, x, y and z have to be observed. If there are many instances of observation available, we can say there is a lot of information. If all three attributes, x, y and z are observed, a person can be very confident of the truth of the belief.

Gill, Swan and Silvera (1998) say this confidence, no matter how high and no matter how well corroborated, does not necessarily mean that what is believed is actually true. Someone who already knows 1, 2 and 3 equals quality A in someone’s books, can simply exhibit traits 1, 2 and 3. While quality A can be corroborated with traits 1,2 and 3, it may also require that traits 4, 5 and 6 be absent. Even if there are abundant observations of 1,2 and 3, there may be insufficient data by design or by circumstance on 4, 5 and 6. What is tragic is because of the limitations of processing capacity and what Hall et al. (2007) termed the illusion of knowledge, even if instances of 4,5 and 6 were observed, it is possible for the observer to gloss over or reason them away so that the mental representation is integrated and intact. Also, it is entirely possible as researchers have shown, to be primed to observe 1,2 and 3.

For these reasons, some tests are not foolproof. Some people love testing. Some people love going through tests because they know how to do well. Some people find them draining and avoid them.

Tests are inevitable and may be the best available way to reduce uncertainty about the future. Gelong Thubten is a monk. His teachings on meditation may be useful for someone who dislikes tests.

A very insightful and liberating nugget in his teachings is that, “we have a habit of pushing away discomfort” (Thubten, 2019). He elaborates, “Pushing things away, however, simply leads to a habit of needing to push away more and more, and so there will always be something to run away from.”

Also, he says that people feel frustrated when there are distracting thoughts when they are trying to focus on their breathing during meditation. This is no different from for example, feeling like watching television when we have to finish a task instead. He explains that meditation is not a trance-like state but a feeling of awareness without judgement. It is about regaining focus. The regaining of control is what makes focus stronger. Therefore, these distractions are in fact necessary so we can practise regaining control. That is the whole purpose of meditation training. Distractions and things which cause discomfort are like resistance which helps build muscle; no resistance, no muscle or no distraction, no need for focus.

The thing about tests is that there are always two sides, the testing side and the tested side. Ideally, the test benefits both the tester and the tested. If the test is solely for the tester’s benefit, say to increase confidence or to confirm a confidently held world-view, or to measure against some benchmark, an instinctual and entirely reasonable response by the tested would be to avoid. This, as Thubten points out can be avoided because avoiding is also as tiring as the test itself.

So, in such circumstances one can say; I am not interested in passing your tests. I am just here to have a good time.

The Brain Dojo